Youri EGOROV

READING

In this section you can check out info related to Youri Egorov’s Death. Do use the 2nd navigation bar to check out the two different Biographies, his Background (photos only ), info regarding his Death, a Timeline, info on the former Youri Egorov Foundation, info on Concert Dates and Articles.Death

Death related items

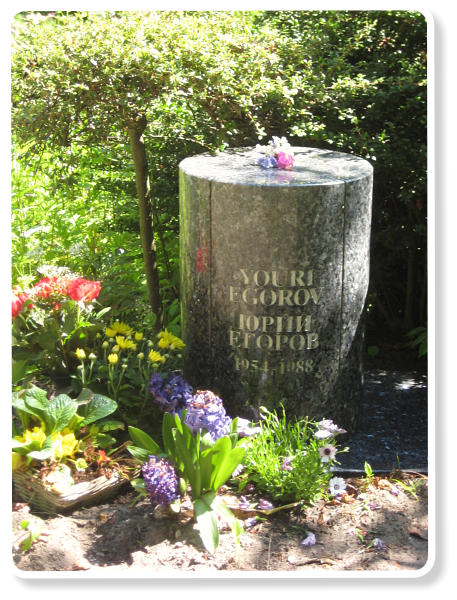

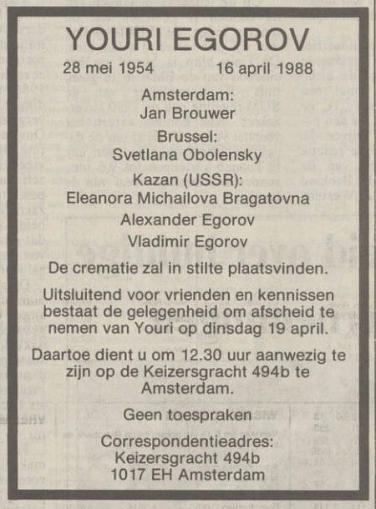

† April 16, 1988

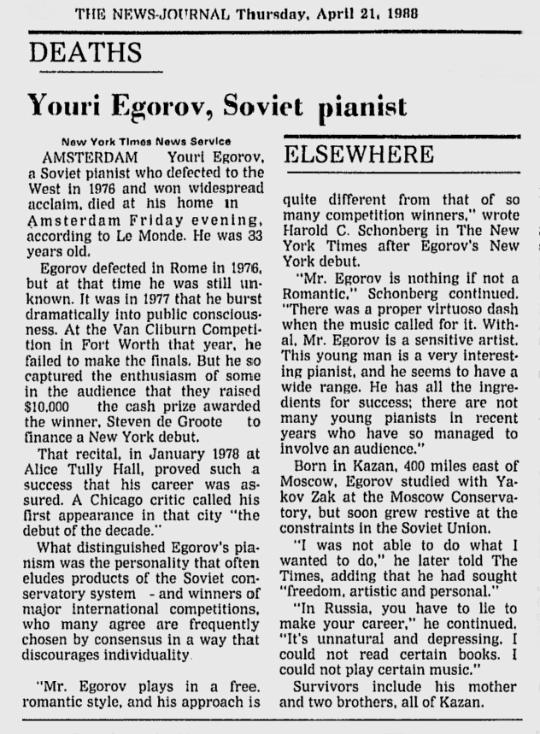

Obituary - De Volkskrant

The New York Times

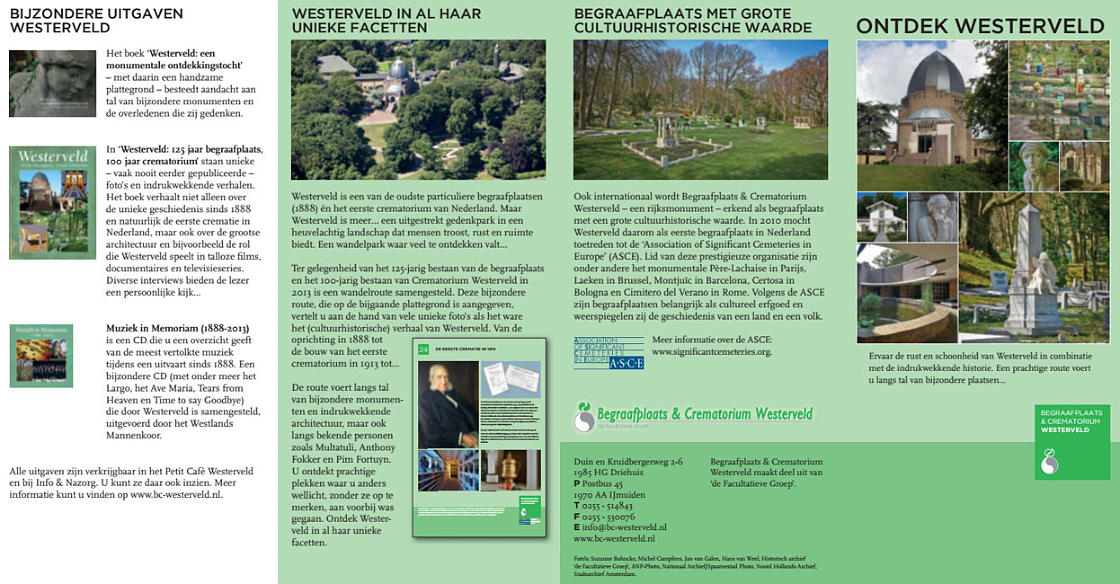

Discover Westerveld Cemetry - the map that guides you along Youri’s urn

Inquirer Music Critic

Courtesy: David Patrick Stearns.

Reprinted with permission of David Patrick Stearns.

Recalling a pianist's fleeting brilliance Classical music's shooting star.

By David Patrick Stearns INQUIRER MUSIC CRITIC

POSTED: August 19, 2008

BY DAVID PATRICK STEARNS

Though the 1970s are recent history amid the passing centuries of classical music, the new EMI boxed

set Youri Egorov: The Master Pianist arrives like something out of a time warp (Oh yeah! Remember

him?), from the era when this young artist was making critics reach for new superlatives and being

mentioned in the same exalted breath as Yo-Yo Ma.

Cute as a puppy dog and blessed with a glistening sonority often compared to the legendary Dinu

Lipatti, Egorov entered all the top contests (Queen Elisabeth, Tchaikovsky) and finally made his name

by not winning the Van Cliburn Competition - he was never that kind of pianistic racehorse. Still, a

band of incensed admirers collected an alternative cash prize, allowing him to make an extravagantly

acclaimed New York debut in 1978.

Ten years later, at age 33, he died, already on the way to being forgotten: He hadn't played in the

United States since 1986 (his local visits being a recital in West Chester and a concerto date with the

Philadelphia Orchestra), while his EMI recording contract concluded with a 1985 visit to Abbey Road

for Mozart concertos with Wolfgang Sawallisch.

He'd had one of the great five-year careers in piano history, but even devoted fans never quite knew

what happened. Bits of his story have come out over the years, and the considerable quality of the

seven-disc EMI box, with early recordings he made in Amsterdam for the Peters International label,

will raise questions anew.

At first, Egorov devised long, ambitious programs - one had the Bartok Piano Sonata plus both books

of Chopin etudes - and his Schumann recordings were compared to the best of the old masters. His

Carnival and Kreisleriana show him at his most demonic, fueled by a technique that didn't seek to

dazzle the ear but took you down a fantastical rabbit hole, through Schumann's inner psyche and

into the world of E.T.A. Hoffmann tales that inspired the music.

No wonder he was one of the few Russian pianists to escape being typecast in repertoire of his own

nationality. Indeed, the ethereal, almost liquid sonority he brought to the final pages of Schumann's

Papillons, Op. 2 presaged what would be his finest recordings of all - the Debussy preludes. It's here

that Lipatti comparisons were replaced by those with the also-legendary Walter Gieseking, though

Egorov's performances show greater concentration and more subtle characterization of the music's

abstract imagery.

Such qualities weren't initially apparent in his 1983 Debussy LPs: Recorded in early, dry digital sound,

they captured maybe half the aura he created in concert. Luckily, the newly remastered CD versions

are greatly improved, projecting an unnervingly complete identification with the music in which

performer and composer merged completely. As in Egorov's Schumann, individual musical

components dissolve into a larger panorama of humanity and imagination. That's partly why his

inhibited, emotionally detached later recordings - Mozart Piano Concertos Nos. 17 and 20 plus

Schumann's Bunte Blatter - seem disappointingly unlike him. Though his interpretive fantasy wasn't

dead - live recordings from his last year are fearlessly personal - it was half slumbering.

Having observed Egorov in numerous concerts, a few interviews and a reception or two, I believe his

decline came from an inability to navigate the music industry's need for consistency and guile. He'd

grown up in provincial Kazan (which explains his Tatar-esque looks) and been educated in Moscow,

where his parents had him live in a monastery to keep him out of trouble (unaware that feast days

involved mandatory around-the-clock drinking, which Egorov said he relished).

The combination of bad habits and sheltered existence perhaps explains why, on seeking political

asylum during a tour in Italy, he cluelessly took his case to the Communist police. Somehow, he was

treated sympathetically, and made his way to Amsterdam (a fine place for practicing bad habits),

where he's said to have been discovered sleeping on a park bench by the man who later became his

partner. Though Egorov's stated reasons for emigrating were political, they in fact had more to with

sexual politics. "Gay bashing" wasn't a common term then, but muggings he described in Moscow

more or less amounted to that.

The West's party mentality of the 1970s, however, didn't bring out the best sides of his character - or

the smartest career decisions. He broke with the U.S. manager, Maxim Gershunoff, who had

discovered him. He was so intimidated by acclaim for his Paris debut that he said, "I can never go

back there again" - meaning admirers had to schlep to places like Elmira, N.Y. Though he was often

seen with entourages of various sizes, friends seemed keenly interested in protecting him from

himself. Upon checking into a hotel, he joked about having to immediately move lamps from tables

to the floor for fear of knocking them off later in the evening. Nice laugh line, except that Egorov's

concerto dates were drying up due to his memory lapses. Venerable Artur Rubinstein could be

forgiven such things, but Egorov wasn't asked back.

His death was widely assumed to be from AIDS. Gershunoff, however, wrote a memoir stating that

Egorov, knowing he had AIDS, chose euthanasia after a farewell dinner in Amsterdam with friends.

It's sad to imagine him making a decision that implies so little faith in the future and so much despair

in the present. One thinks of harpsichordist Scott Ross, who died of AIDS in 1989 but spent his final

years with a home recording studio, taping d'Anglebert on days when he felt well enough.

But then, Egorov lacked the fallback mechanisms of many seasoned artists. He didn't have the Midas

touch that allows performers to put an ingratiating gloss even on works they haven't lived with for

long. Though all performances are different from each other in theory, if not in fact, Egorov's were

varied more than most, almost to the extent that, within certain boundaries, he seemed to reinvent a

piece with each encounter. The weight and color he gave to a phrase could never be predicted. But

even a coughing audience could leave him undone, in what seemed like a fragile, complex musical

mechanism. It can't have been easy to live with. But without it, we would never have had his Debussy.

Contact music critic David Patrick Stearns at dstearns@phillynews.com